“The guard is the salvation of the weak,” said Rilion Gracie in a GRACIEMAG interview in February 2009. Well today, after wins from stars Fabricio Werdum (in Strikeforce) and Anderson Silva (in the UFC), everyone seems to understand a little better just how important Jiu-Jitsu’s leg game is in a fight situations.

Whether you are an MMA fighter looking to avoid getting put through a family-sized wringer, a Jiu-Jitsu competitor or impassioned practitioner, you need to delve deeper into the concept of the guard to evolve in training. So revisit what Rilion taught us last year, and don’t miss the next GRACIEMAG.

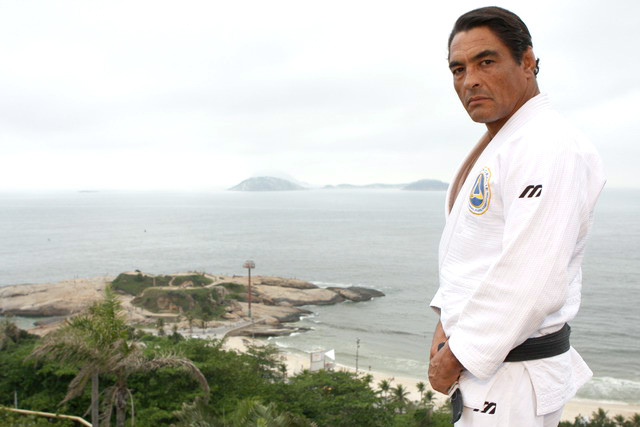

Rilion observes. Photo: Ray Santana.Rickson Gracie always said you have the best guard of the family. What makes a guard good?

The guard has always been a way of evening the playing field in a fight between two people, bringing the fight to the ground, where a 60kg guy balances out the strength difference and even goes on to have better chances of surprising the 120kg guy.

When I got my black belt, 25 years ago, I weighed 59kgs. And I always had the winning spirit, understood my family’s Jiu-Jitsu to be an art of self-defense, but one with the objective of submitting the adversary. The same way these days we see hundreds of scrawny guys, with good guards for lack of other options, the same went for me. The guard is the salvation of the weak.

How did you go about developing your game?

Guided by Rolls, Carlinhos, Rickson, Crolin, professors who I mirrored, I realized I had to have a really good guard to face anyone, but a complete guard – I wasn’t interested in just holding out against opponents, defending myself without managing to do anything in the fight. But the first idea that clicked for me, at blue belt, was: if I can’t manage to neutralize the guy with the guard, with which I have millions of options of barriers, my legs and hands and all, if he passes I’m dead – I have to exert triple the force, and on top of that with the guy’s weight on my chest, squashing my neck, ears. So my first concern is not to lose.

And what would be the second stage?

At purple belt I was already real flexible, and with a guard famed for being unpassable, at the little championships. But it happens that I’d win because the guy on top would wear out, and ended up leaving openings for the triangle, or I’d end up on his back and such. So, I went on to the next stage, developed at brown: to reconcile defensive with attacking guard, incorporating a varied game of submissions from the guard, sweeps and taking the back. That’s when my Jiu-Jitsu started improving on all fronts, because I started landing on top of my adversary, and I had to make the most of the favorable situation. These days, I think I’m better on top than on the bottom. I prefer playing on top – my objective is to jump the fence and attack my adversary.

I specialized in leaving an opening for the guy to pass, as that is the moment he exerts force – and so he wears out and falls in a trap” Rilion

What other tricks do you have for making adversaries fall into traps in the guard?

One kind of guard is that where you grab onto the sleeves, tie up the guy’s arms, but you can’t do anything either, and it becomes an ugly fight. Another is the guard where you give the guy a little taste. He sees his chance to pass, exerts force but doesn’t pass. I specialized in that, in leaving openings for the guy to pass – and there he either exerts force and tires, or falls into some trap.

Because I don’t believe there are humans who don’t tire. The best prepared guy in the world, confronted with the right technique, executed to perfection, he will be forced to apply force, and at some point will wear out. Everyone has their limit, it’s up to you to find the method and path to pushing your adversary to it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQqaU-Vw2ro

Which is your favorite guard?

Jiu-Jitsu to me is easy and effective. It’s that which you can teach any student who walks into your gym, otherwise they’ll pick up their things and never come back.

I look to play guard right at the guy, at least in my way of fighting. I try to keep the guy worried about getting submitted the whole time, fearing getting tapped out. Even if the guy knows how to defend, the worry will fatigue him, exhaust him. And when he makes a mistake, he gets caught. The better your adversary’s technique, the more you need to worry him.

So of course, I’ll even play half-guard, sometimes. But, if the adversary is really good, after I sweep him he will still put up a fight from the bottom. So then one gets a sweep here, the other gets one there, and then it becomes that fight we’re seeing in competition these days. Of course, you need to know your objective when playing guard. If it’s to sweep for points, perfect. But I don’t want my opponent only to be concerned with not getting swept. He has to feel threatened the whole time.

Is there any bad type of guard?

I respect all positions. If I teach a technique to ten different people, I know that, as much as I’d like it to be otherwise, each student will be more suited to one aspect and not the other. Jiu-Jitsu is an infinite art; a shorty won’t have the same game as someone with long legs. That’s why a master can’t go blindly labeling one guard bad and the other good. The secret is to make out the weaknesses and virtues of the position, never condemn, arrogantly. Now, the guy who wants to be a reference in the guard cannot just know one guard. He has to know other paths, for the day he encounters a rock in his way.

Jiu-Jitsu is sensibility” Rilion

What’s your challenge these days, when training?

To conserve more energy than before. I’m better technically, more experienced, but I’m not the Rilion of fifteen years ago. I feel good for my age, of course, and know a Rilion of 35 would fatally defeat a Rilion of 25. But nowadays, at 45, I don’t recover as quickly as I did. Back in the day I’d push the pace, take two breaths and be ready to go again for 20, 30 rolls. I know physically I’m in the process of decay. At the same time, the more flight time, the more microscopic subtleties you have. For example, you start developing a sensibility where you can guess your adversary’s thoughts. A second before the guy makes a move your hook is in there blocking him. That’s what Jiu-Jitsu’s about. Without sensibility, without a certain spiritual connection to the art, you win on conditioning, durability, and you’ll always be coarse, someone with ugly style.

Your brother Rolls Gracie (1951 – 1982) is seen as the bridge between modern and classical Jiu-Jitsu. Was he also the link between the guard of the past and the modern guard?

Without a doubt. When Jiu-Jitsu fell into Rolls’s hands, it evolved 50 years in ten. He took a Beetle and made it into a Ferrari, and dropped it in our hands. Of course, the wheel, headlights already existed. But it was with Rolls that the guard went from being defensive, waiting for the opponent, to a position with an arsenal of attacks.

He had a really open and dynamic mind, always paid attention to the student, and liked listening to them, to see new positions. Now you take a guy in the spotlight and it seems you have to plead for the love of God for him to teach you a position. So it was Rolls who created what was, to me, the golden generation of Jiu-Jitsu: Carlinhos, Crolin, Rickson and so many of Rolls’s students from outside the family.

I learned a lot about the guard watching one of them train, a guy called Talarico, who even had short legs.

Liked what you read and want to learn more every month? Then click here to subscribe to GRACIEMAG.