[First published in 2013. Scroll down for plain text.]

=====

Text: Raphael Nogueira / Photos: Gustavo Aragão

Cover

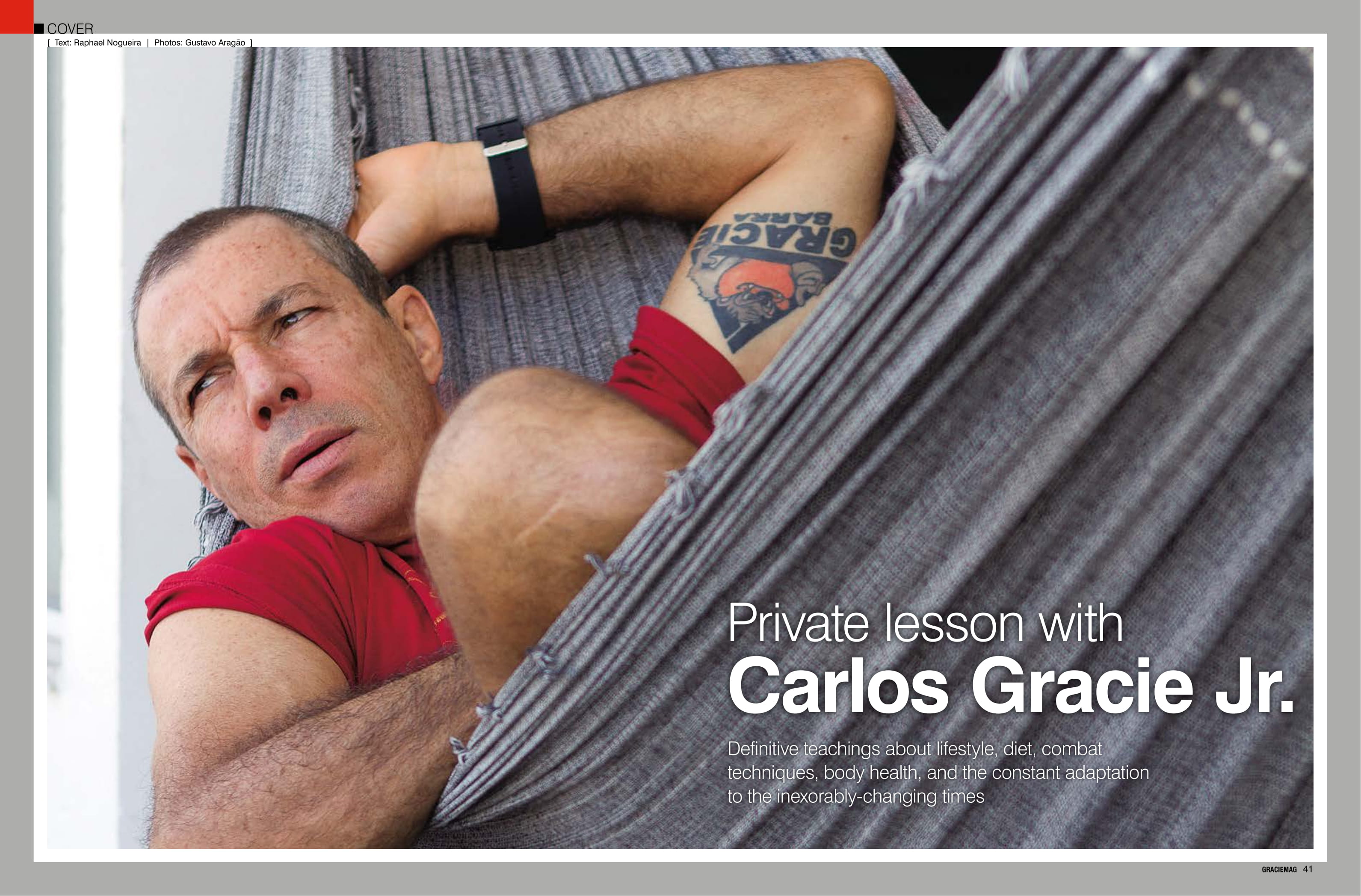

Private lesson with Carlos Gracie Jr.

Definitive teachings about lifestyle, diet, combat techniques, body health, and the constant adaptation to the inexorably-changing times

It’s ten-twenty at night. Carlos Gracie Jr. wants to eat dinner. While he talks to a reporter and a photographer from GRACIEMAG, the 57-year-old master examines the papayas on the kitchen countertop in his Florianópolis, Brazil home. He squeezes the fruits, feels their softness, brings one by one close to his nose to make sure they’re really ripe. And he goes on speaking. He slices the papayas, uses a spoon to get rid of the seeds and get the pulp from the fruits. Never does his professional tone leave him as he handles the questions thrown at him by the reporter. Those are technical questions on Jiu-Jitsu, minutiae about the “open guard with hand on collar,” one of Carlinhos’s favorite positions.

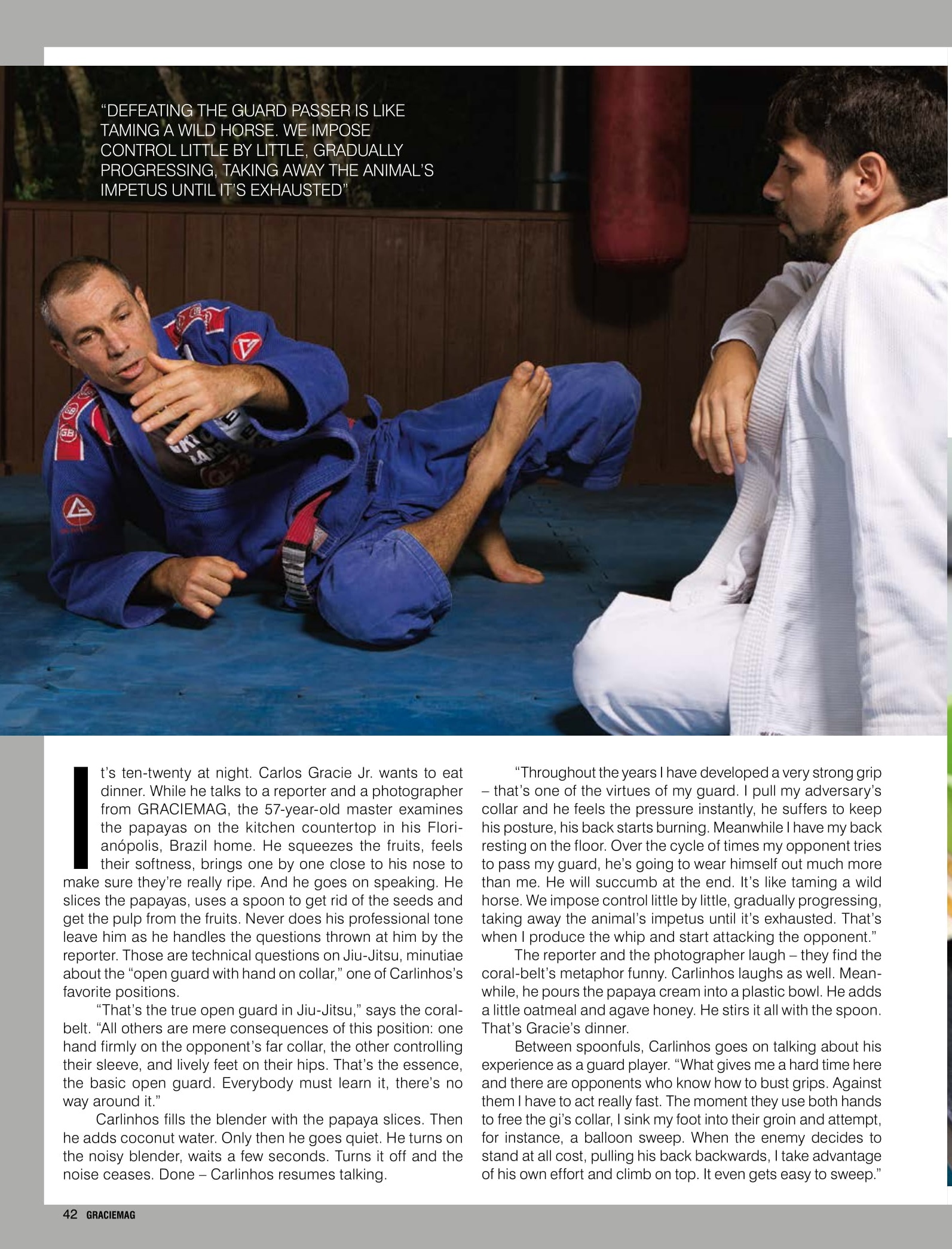

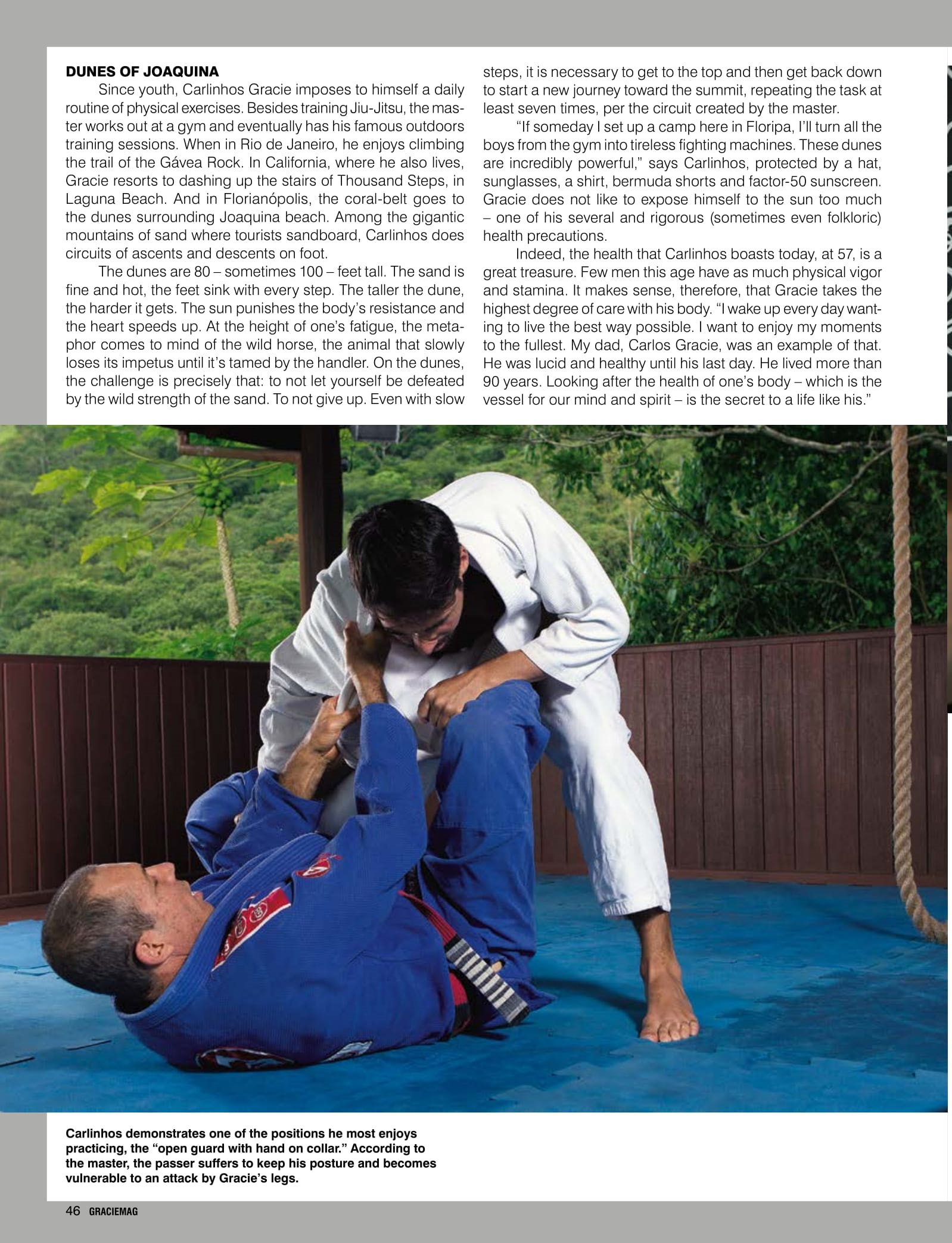

“That’s the true open guard in Jiu-Jitsu,” says the coral-belt. “All others are mere consequences of this position: one hand firmly on the opponent’s far collar, the other controlling their sleeve, and lively feet on their hips. That’s the essence, the basic open guard. Everybody must learn it, there’s no way around it.”

Carlinhos fills the blender with the papaya slices. Then he adds coconut water. Only then he goes quiet. He turns on the noisy blender, waits a few seconds. Turns it off and the noise ceases. Done – Carlinhos resumes talking.

“Throughout the years I have developed a very strong grip – that’s one of the virtues of my guard. I pull my adversary’s collar and he feels the pressure instantly, he suffers to keep his posture, his back starts burning. Meanwhile I have my back resting on the floor. Over the cycle of times my opponent tries to pass my guard, he’s going to wear himself out much more than me. He will succumb at the end. It’s like taming a wild horse. We impose control little by little, gradually progressing, taking away the animal’s impetus until it’s exhausted. That’s when I produce the whip and start attacking the opponent.”

The reporter and the photographer laugh – they find the coral-belt’s metaphor funny. Carlinhos laughs as well. Meanwhile, he pours the papaya cream into a plastic bowl. He adds a little oatmeal and agave honey. He stirs it all with the spoon. That’s Gracie’s dinner.

Between spoonfuls, Carlinhos goes on talking about his experience as a guard player. “What gives me a hard time here and there are opponents who know how to bust grips. Against them I have to act really fast. The moment they use both hands to free the gi’s collar, I sink my foot into their groin and attempt, for instance, a balloon sweep. When the enemy decides to stand at all cost, pulling his back backwards, I take advantage of his own effort and climb on top. It even gets easy to sweep.”

Light digestion

The papaya cream is gone before long. But the master continues to scrape the bowl with the spoon, signaling he is still hungry. It’s an interesting moment in Carlinhos’s meal. Despite being hungry, he doesn’t want to binge. There’s a preoccupation with not going overboard, a true rigor toward the amount of food ingested and, consequently, the quality of the upcoming digestion.

Gracie gets up, goes to the kitchen and washes the plastic bowl in the sink. Then he opens the fridge and gets three eggs. He puts them in a pan with water and lets them cook for a few minutes. While the water boils, Carlinhos talks about the guards that have been getting attention in recent championships.

“I don’t get this obsession with all the acrobatic guards. They are efficient, sure. But they’re fleeting. Your body has difficulty withstanding them for too long. I say this from my own experience. The lumbar region, for example, as strong as it may be, will never be armored against the passage of time. Jiu-Jitsu is for your whole lifetime, and by that line of reasoning you can rest assured that the basic techniques, like the closed guard or this open guard I enjoy doing, will never abandon us. At 70 we’ll still be capable of performing them with plenty of mobility. That can’t be said of the tornado guard or the berimbolo.”

The eggs are done. Carlinhos pours the boiling water in the kitchen sink, lets the eggs cool down for a few seconds under the tap water, and begins to peel them. Then he takes the yolks out of each one and eats only the whites. No salt, no toast. Just the whites. Done. Now he’s sated. And light. None of that sluggishness that so often takes over the bodies of those who opt for heavy meals and ill-advised mixtures.

The master points to the papayas left on the countertop and asks the GRACIEMAG staff (guests in Gracie’s home for three days): “Do you guys want dinner as well?” Carlinhos goes up the wide staircase that leads to the second floor – he wants to play a bit with his youngest son, the frolicsome Kayan, before bed. “Just don’t make a big mess in the kitchen,” warns the master. “Sleep tight. Tomorrow I’m taking you two to see the dunes.”

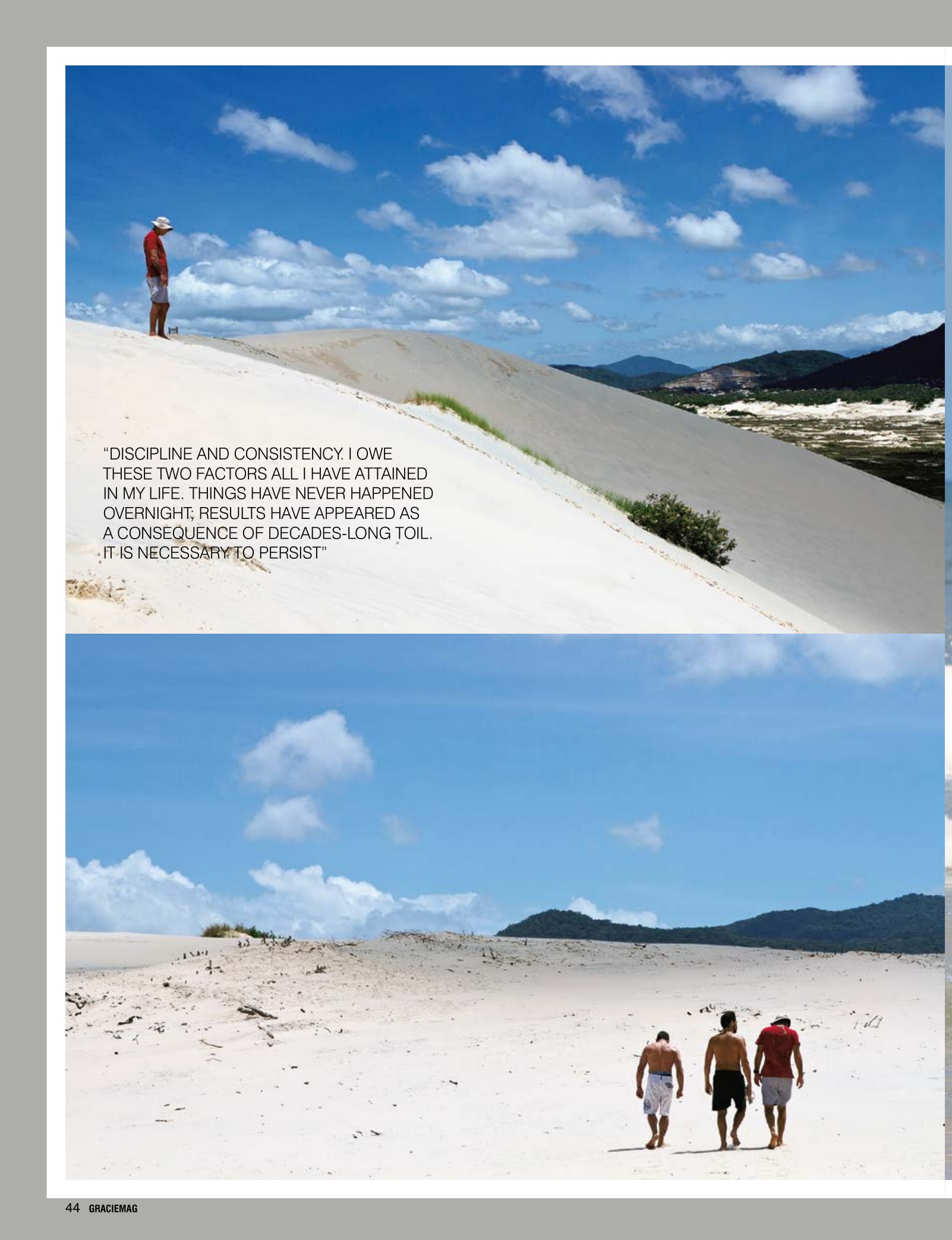

Dunes of Joaquina

Since youth, Carlinhos Gracie imposes to himself a daily routine of physical exercises. Besides training Jiu-Jitsu, the master works out at a gym and eventually has his famous outdoors training sessions. When in Rio de Janeiro, he enjoys climbing the trail of the Gávea Rock. In California, where he also lives, Gracie resorts to dashing up the stairs of Thousand Steps, in Laguna Beach. And in Florianópolis, the coral-belt goes to the dunes surrounding Joaquina beach. Among the gigantic mountains of sand where tourists sandboard, Carlinhos does circuits of ascents and descents on foot.

The dunes are 80 – sometimes 100 – feet tall. The sand is fine and hot, the feet sink with every step. The taller the dune, the harder it gets. The sun punishes the body’s resistance and the heart speeds up. At the height of one’s fatigue, the metaphor comes to mind of the wild horse, the animal that slowly loses its impetus until it’s tamed by the handler. On the dunes, the challenge is precisely that: to not let yourself be defeated by the wild strength of the sand. To not give up. Even with slow steps, it is necessary to get to the top and then get back down to start a new journey toward the summit, repeating the task at least seven times, per the circuit created by the master.

“If someday I set up a camp here in Floripa, I’ll turn all the boys from the gym into tireless fighting machines. These dunes are incredibly powerful,” says Carlinhos, protected by a hat, sunglasses, a shirt, bermuda shorts and factor-50 sunscreen. Gracie does not like to expose himself to the sun too much – one of his several and rigorous (sometimes even folkloric) health precautions.

Indeed, the health that Carlinhos boasts today, at 57, is a great treasure. Few men this age have as much physical vigor and stamina. It makes sense, therefore, that Gracie takes the highest degree of care with his body. “I wake up every day wanting to live the best way possible. I want to enjoy my moments to the fullest. My dad, Carlos Gracie, was an example of that. He was lucid and healthy until his last day. He lived more than 90 years. Looking after the health of one’s body – which is the vessel for our mind and spirit – is the secret to a life like his.”

Armored against criticism

After the workout on the dunes, a dip in the icy waters of Joaquina beach is a must. As he approaches the sea, Carlinhos is recognized by pupils chatting in circles on the sand. They yell the master’s name, wave from afar. Gracie has great prestige in Floripa. There’s always a student or fan who comes by to shake the coral-belt’s hand, exhibiting a mixture of awe and gratitude.

Of course, like everybody (especially those in leadership positions), Carlinhos has his detractors. But these are such favorable times to Gracie’s prestige, that even Wallid Ismail, a notorious critic regarding the paths taken by the CBJJ and the IBJJF (both presided by Carlinhos), recently praised the coral-belt. On page 16 of this issue, for example, Wallid says: “I’ve criticized profusely, I didn’t recognize the great work Carlinhos was doing. I don’t regret it – I was fighting for my ideals, – but today I recognize that the work of organizing Jiu-Jitsu was very well done. The precursors deserve to be in charge.”

Since the beginning of his career, Carlinhos has been good at dealing with criticism. He had to earn that skill the hard way; after all, it’s a basic requirement for those who like to think big and set out to make challenging dreams come true. Besides the CBJJ and IBJJF, Carlinhos founded the Gracie Barra network, deemed the biggest chain of Jiu-Jitsu academies in the world; he has formed over 350 black-belts, and he founded GRACIEMAG, which celebrates 200 issues this month.

If he had feared the critiques he heard as he implemented each of these creations, Carlinhos would have given up in a flash, thwarting his dreams. Gracie, however, breathed deep, withstood the pain and thought fast under pressure, assimilating what was constructive about the attacks and jumping over hurdles as well as he could. Through intuition, he has always believed in success in the long term.

There was a time when the weigh-ins for CBJJ events were held in the living room of the home where Carlinhos lived with his wife and kids in Rio de Janeiro. And the master is not ashamed to recollect these precarious, even laughable stretches when you compare them to the current structure of the CBJJ and, especially, the IBJJF, which hosts impeccable competitions for more than 5,000 athletes, with enrollment open to practitioners of every country.

On the way back from the beach, on Carlinhos’s pickup truck, the reporter and the photographer hear the coral-belt say: “Discipline and consistency. I owe these two factors all I have attained in my life. Things have never happened overnight; results have appeared as a consequence of decades-long toil. It is necessary to persist, and that is something difficult to teach nowadays, a time when society displays so much hunger for immediate rewards.”

Euphoria and serenity

The truck flows freely through the streets of Floripa, not facing any traffic jams. A soft wind enters the vehicle through the small opening in the windows. Carlinhos’s two eyes are lost beyond the windshield. He’s been silent for some ten minutes. The reporter can’t guess what goes through Gracie’s mind in this moment of introspection, but, were he to venture a guess, he’d say Carlinhos has let himself go with memories of the late 1970s – more precisely, flashes of that business-as-usual day when he got his black belt.

The story (almost a legend) is sensational. Late grandmaster Helio Gracie purportedly looked at Carlinhos and said: “Starting tomorrow you may come in wearing the black belt.” That simple. No ceremony, much less a speech. It was something natural, on a day like any other at the gym. The consequence of a long endeavor. Deep down, glory, a great realization – but wrapped in a package of martial simplicity.

Maybe that speaks volumes about Carlinhos’s success. An art of not creating great expectations and, consequently, not getting knocked down by great frustrations. A serene technique of not letting oneself get seduced by dazzle or euphoria. Living for what one loves, always with the maximum possible dedication. The fruits that flourished from that start being absorbed nonchalantly, without any torrents of vanity, or syndromes of paralyzing conquests. After all, how many people reach a goal, find a comfort zone, and then sit there until they die?

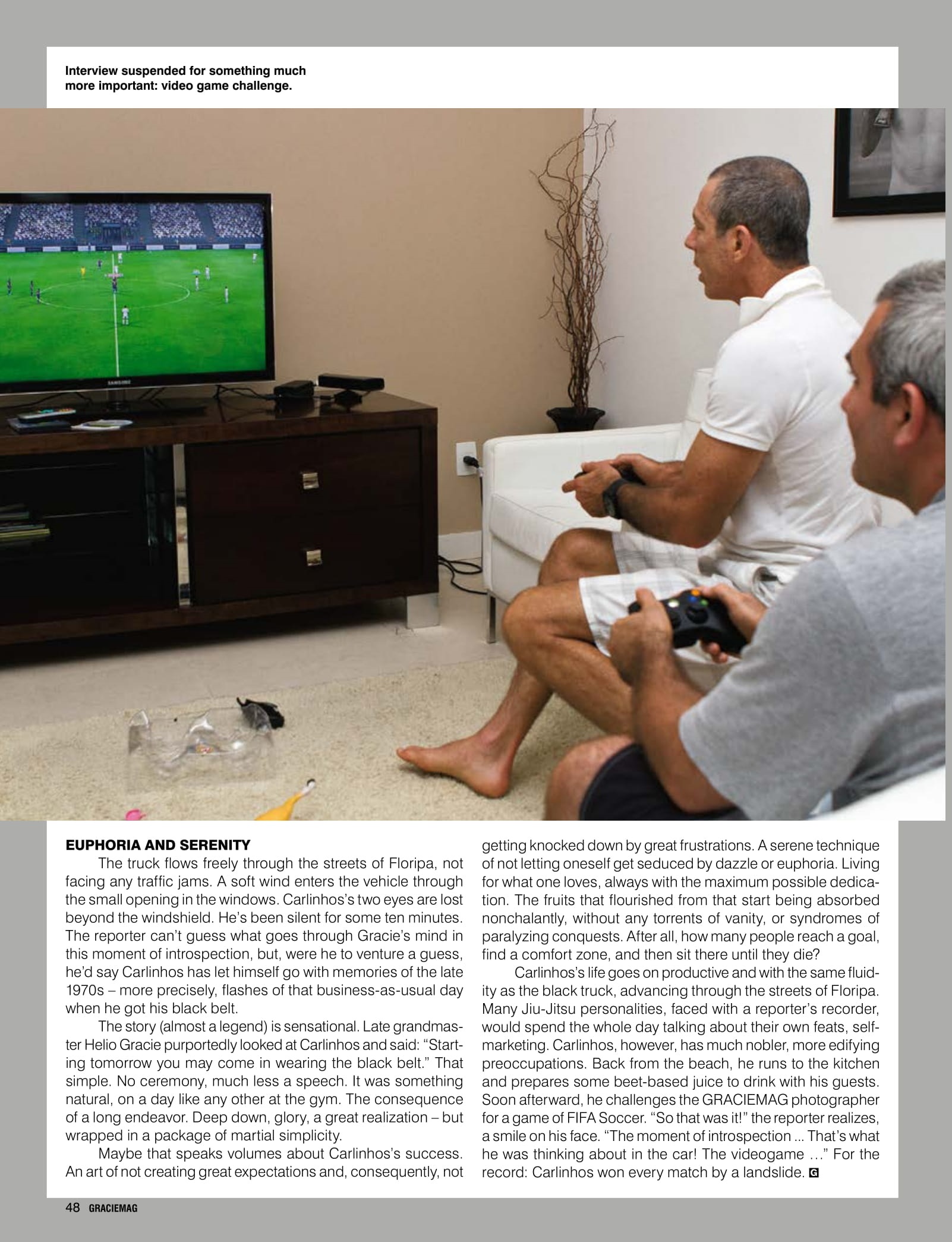

Carlinhos’s life goes on productive and with the same fluidity as the black truck, advancing through the streets of Floripa. Many Jiu-Jitsu personalities, faced with a reporter’s recorder, would spend the whole day talking about their own feats, self-marketing. Carlinhos, however, has much nobler, more edifying preoccupations. Back from the beach, he runs to the kitchen and prepares some beet-based juice to drink with his guests. Soon afterward, he challenges the GRACIEMAG photographer for a game of FIFA Soccer. “So that was it!” the reporter realizes, a smile on his face. “The moment of introspection … That’s what he was thinking about in the car!” For the record: Carlinhos won every match by a landslide.