The history of jiu-jitsu

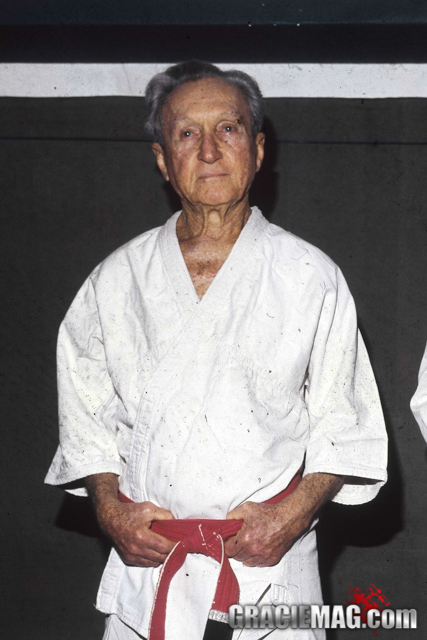

Carlos Gracie. Photo: Marco Imperial

A brief history of the gentle art, from the samurai to the UFC champions and IBJJF gold medalists

Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu or BJJ (also written as jujitsu or jujutsu) is a martial art of Japanese origin in which one essentially uses levers, torsions and pressure in order to take one’s opponent to the ground and dominate them. Literally, jū in Japanese means ‘gentleness,’ and jutsu means ‘art,’ ‘technique.’ Hence the literal translation by which it’s also known, the ‘gentle art.’

Its secular origin, as with almost all ancient martial arts, cannot be pinpointed precisely. Similar fighting styles have been verified in many peoples, from India to China, in the 3rd and 8th centuries. What is known is that its environment of development and refinement were the schools of the samurai, the warrior caste of feudal Japan.

Its creation derives from the fact that, in the battlefield or during any confrontation, a samurai could wind up bereft of his swords of spears, at which point he would need a weapon-less method of defense. Since traumatic strikes were not sufficient in this type of showdown, as the samurai wore armor, the takedowns and torsions began gaining ground due to their efficiency. Thus Jiu-Jitsu was born in contraposition to kenjitsu and other so-called rigid arts, wherein the combatants wielded swords and other weapons.

The martial art gained new dimensions when a celebrated instructor from the Kodokan Japanese school decided to travel the world and prove the efficiency of his choke and armlocks against opponents of all sizes and styles: Mitsuyo Maeda, a sumo fighter’s son born in Funazawa Village, located in Hirosaki City, in the Japanese prefecture of Aomori, on November 18, 1878, and deceased in Belém, capital of the Brazilian state of Pará, on November 28, 1941.

A lifelong champion of Jiu-Jitsu’s self-defense techniques, Maeda traveled to the U.S. in 1904 accompanied by other teachers from Jigoro Kano’s school. At the time, thanks to the political and economic bonds between Japan and the U.S., the Japanese techniques had many a noteworthy admirer on American soil. In 1903, for example, President Theodore Roosevelt had taken lessons from Yoshiaki Yamashita. In the U.S., the agile Japanese man began racking up thousands of combats and fallen opponents along the way in England, Belgium and Spain, where his poise resulted in the nickname by which he became better-known, Count Koma. Back in America, the fighter did many presentations and challenges in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile and Argentina. In July 1914, the valiant 5-foot-5, 68kg fighter landed in Brazil to settle down and change the sport’s history.

A lifelong champion of Jiu-Jitsu’s self-defense techniques, Maeda traveled to the U.S. in 1904 accompanied by other teachers from Jigoro Kano’s school. At the time, thanks to the political and economic bonds between Japan and the U.S., the Japanese techniques had many a noteworthy admirer on American soil. In 1903, for example, President Theodore Roosevelt had taken lessons from Yoshiaki Yamashita. In the U.S., the agile Japanese man began racking up thousands of combats and fallen opponents along the way in England, Belgium and Spain, where his poise resulted in the nickname by which he became better-known, Count Koma. Back in America, the fighter did many presentations and challenges in El Salvador, Costa Rica, Honduras, Panama, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Chile and Argentina. In July 1914, the valiant 5-foot-5, 68kg fighter landed in Brazil to settle down and change the sport’s history.

Maeda would go on to collect delicious stories on Brazilian land. After going around the country, the Jiu-Jitsu black-belt settled in Belém. One day he took on the challenge of a capoeira artist known as Pé de Bola, towering over the master at 6-foot-3 and nearly 100kg. Maeda was not impressed and even let his rival bear a knife in the match. The Japanese disarmed, took down and finished off the Brazilian. Count Koma, as later became a tradition among Jiu-Jitsu professors, would also challenge famous boxers. American boxer Jack Johnson was called out, but never accepted the invite.

Koma and crew in Cuba, 1912. Fabio Quio collection

It was Koma, also, who promoted the first Jiu-Jitsu tournament in the country – more accurately a festival of bouts and challenges designed to give notoriety to the unknown sport.

Researchers Luiz Otávio Laydner and Fabio Quio Takao found in the newspaper Gazeta de Notícias of March 11, 1915 the rules of the event slated for the Carlos Gomes Theater in Rio de Janeiro, then the country’s capital. In it Koma published the first rules of our Jiu-Jitsu, consisting of ten items:

“1. Every fighter must present themselves decently, with fingernails and toenails perfectly trimmed;

“2. They must wear the gi, provided by Count Koma;

“3. It is forbidden to bite, scratch, head-butt or punch;

“4. When the athlete uses their foot, they must never use its tip, but instead the curve;

“5. The fighter whose back is on the ground is not defeated, even if they were the first one to fall;

“6. The fighter who is defeated must signal their forfeit by tapping either the mat or their opponent’s body thrice;

“7. The referee will deem defeated the fighter who, due to some contingency, cannot remember to tap to signal their forfeit;

“8. The matches will be divided into rounds of five minutes with two-minute resting periods interposed between them. The referee will count the minutes aloud for the benefit of the audience;

“9. If the fighters fall off the mat without either one having forewarned of it, the referee must force them to return to the center of the mat, standing and facing one another;

“10. The jurors may replace the referee in his duties. Neither the enterprise nor the winning fighter is responsible for whatever harm may befall the loser if, due to tenacity, that fighter refuses to signal forfeit.

“* Medical doctors, members of the local press, and professors of physical education and fencing are invited to take part in the jury.”

In 1917 a teenager named Carlos Gracie (1902–1994) saw for the first time, in Belém, a display by the Japanese man who was capable of dominating and submitting the area’s giants. A friend of his father, Gastão Gracie, Maeda agreed to teach the restless boy the art of defending oneself. In his lessons, he would teach Carlos and other Brazilians – like Luiz França, future master to Oswaldo Fadda – the concepts of his art: on the feet or the ground, the opponent’s strength was supposed to be a weapon for the win; to approach the adversary, low kicks and elbow strikes were to be the stratagems before taking them down. For evolution in training, he would use the randori, a full-on sparring session with a partner.

A faithful student, Carlos Gracie embraced Jiu-Jitsu and, to the heartbreak of the mom who dreamed of seeing more diplomats in the prestigious family, he started infusing his brothers with the love for the art. One of eight siblings (Oswaldo, Gastão Jr., George, Helena, Helio, Mary and Ilka), in 1925 Carlos opened the Gracie family’s first BJJ academy. The ad in the newspaper was a marketing masterpiece: “If you want to have your arm broken, look for the Gracie Academy.”

The grandmaster would go on to spawn 21 offspring, 13 of whom became black-belts. Each member of the family began, then, strengthening the art and adding one more link to the chain created by Grandmaster Carlos, founder and guide of the clan, as well as first in the family to launch himself in a rule-less fight, which he dubbed vale-tudo. It was in 1924 in Rio de Janeiro that Carlos Gracie confronted stevedore Samuel, a renowned athlete of capoeira.

Helio quickly became the standout among the brothers due to the technical innovations he made as an instructor and the indomitable spirit that was at odds with his skinny body. In consonance with the tactics of Count Koma, the Gracies continued challenging capoeira artists in Rio, as well as stevedores and other brave men of all origins and sizes. If these muscle men looked fearsome on their feet, on the ground they became easy prey to the pounces and chokes that defeated them as if by magic.

The family’s victories in no-rules matches started becoming legends and front-page stories, and mounting. The famous pupils, also – artists, architects, state ministers, mayors, governors, surgeons and doctors from every field.

Besides the challenges, the championships featuring practitioners, with rules exclusive to Jiu-Jitsu, were gaining momentum, fueled by rivalries of dozens of different academies. In the 1960s, when Carlson Gracie had already taken his uncle Helio’s baton as the clan’s front line in vale-tudo, an important step was taken towards the consolidation of sport Jiu-Jitsu. In 1967 the Guanabara Jiu-Jitsu Federation, in Rio, was created under the authorization of the country’s National Sports Confederation. Among the still-primitive rules, moves like takedowns, frontal mounts with both knees on the ground and the back-take yielded one point. Match duration for the adults category was set at five minutes, with three minutes’ overtime. Jiu-Jitsu had gained time controls and a scoring system.

The president of the Federation was Helio Gracie, and the president of the Consultative Council was Carlos. His first-born, Carlson, was director of the technical department. The first technical vice-director was Oswaldo Fadda, and the second was Orlando Barradas – both of them Jiu-Jitsu professors. João Alberto Barreto, a notable pupil of the Gracies’, was named director to the teaching department, whose vice-director was one of Carlson’s brothers, Robson Gracie – each of them a grandmaster of the art nowadays.

In the ’90s the art underwent a new boom. On two fronts: created by Rorion Gracie in 1993, the Ultimate Fighting Championship kick-started the sport known today as MMA. Starting with pioneer Royce Gracie and further consolidated through the sweat of a bevy of his cousins and brothers in Rickson, Renzo, Ralph, Royler, Ryan, Carley and company, Jiu-Jitsu as a method of self-defense had nothing more to prove.

On another front, Carlos Gracie Jr. picked up his father’s work organizing championships and strengthening the art as a regulated sport. Thus the International Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu Federation (IBJJF) was created in 1994, and these days it promotes tournaments overflowing with over 3,000 athletes from more than 50 countries, such as the World Championship, held annually since 1996.

One century after Count Koma disembarked in Brazil, our Jiu-Jitsu today can be practiced from Alaska to Mongolia, from Abu Dhabi to Japan.

The rest of this story continues to be written by each white-belt who steps into a Jiu-Jitsu gym for the first time.

To learn BJJ straight from Renzo Gracie, a fighter whose name is etched on the history of BJJ and MMA, visit the Renzo Gracie Online Academy.

If you want to help us keep the lights on and create more content like this article, support us.